How a $57 billion value destruction teaches us about category dynamics, consumer velocity, and the limits of operational excellence

Executive Summary

The Wall Street Journal reports that Kraft Heinz is planning to break itself apart, marking a dramatic reversal of the 2015 mega-merger orchestrated by Warren Buffett and Brazilian private equity firm 3G Capital. The company plans to spin off its grocery business (including Kraft products) into a new entity valued at up to $20 billion, while retaining faster-growing sauces and condiments like Heinz ketchup and Grey Poupon mustard.

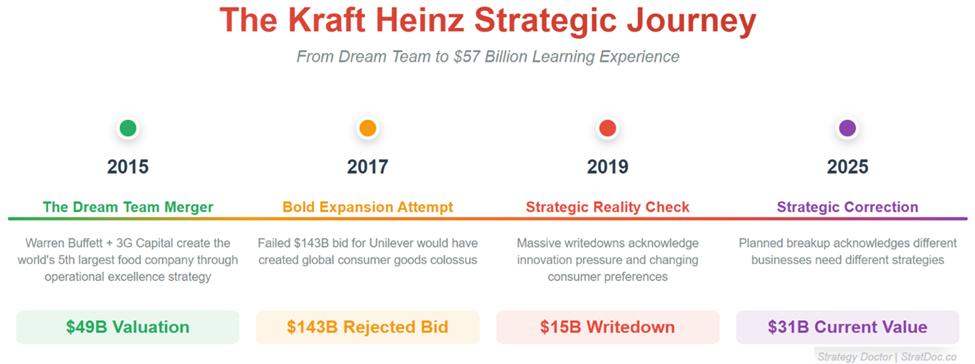

This breakup represents more than corporate restructuring—it’s the acknowledgment of one of business history’s most expensive lessons in strategic timing. Since the 2015 merger, Kraft Heinz stock has fallen over 60%, erasing $57 billion in market value.

The timing couldn’t be more relevant. As the Wall Street Journal reports, big food companies are facing a reckoning as inflation-weary consumers balk at sharply higher grocery prices, hunt for deals, and switch to store-brand goods. Heightened government scrutiny over processed food, the rise of weight-loss drugs, and growing consumer preferences for fresher, healthier fare are compounding these challenges.

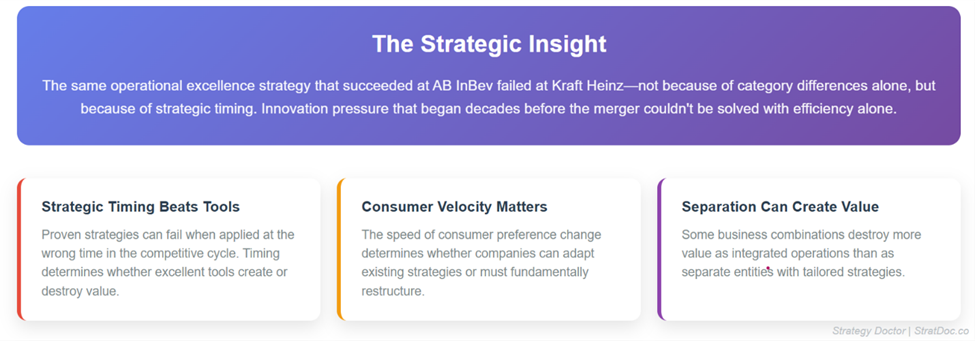

The deeper strategic insight: This value destruction becomes particularly instructive when viewed through the lens of strategic sequencing rather than simple category mismatch. While the same operational excellence strategy succeeded at AB InBev and Burger King, it encountered different dynamics at Kraft Heinz—not because of category differences alone, but because of strategic timing. Kraft Heinz encountered decade-old innovation pressure precisely when implementing efficiency measures, while 3G’s beer success benefited from innovation waves that emerged after operational excellence was established.

Figure 1. The Kraft Heinz Strategic Journey 2015-2025

The Breakup: What’s Happening Now

Kraft Heinz is preparing to separate into two distinct entities, each optimized for different competitive dynamics:

SpinCo (Grocery Business)

- Valued at up to $20 billion

- Includes Kraft-branded products: mac and cheese, processed lunch meats, Maxwell House coffee

- Focuses on value optimization and operational efficiency

- Targets price-sensitive, convenience-focused consumers

RemainCo (Condiments & Sauces)

- Houses Heinz ketchup, Grey Poupon mustard, hot sauces

- Faster-growing, higher-margin products

- More aligned with current consumer preferences

- Greater innovation and premium positioning opportunities

The Strategic Rationale

The split acknowledges what should have been evident in 2015: these are fundamentally different businesses requiring incompatible strategies. Using Michael Porter’s strategic positioning framework, grocery staples compete primarily on operational effectiveness (price and convenience), while condiments and sauces can achieve strategic positioning through differentiation and innovation.

The combined entity aims to unlock value exceeding Kraft Heinz’s current $31 billion market capitalization by enabling each business to pursue its natural competitive advantages without strategic compromise—a classic application of the portfolio strategy principle, which suggests that diversified companies often trade at a discount to the sum of the value of their parts.

Historical Context: The 2015 “Dream Team” Strategy

In 2015, the Buffett-3G partnership appeared to represent the perfect marriage of patient capital and operational excellence. Their resource-based view logic was compelling:

Proven Track Record

- AB InBev: Built the world’s largest beer company through acquisitions and cost-cutting, reaching $40 billion in revenue

- Burger King: Doubled cash flow from $250M to $700M in three years through refranchising and zero-based budgeting

- Restaurant Brands International: Successfully integrated Tim Hortons into growing QSR empire

Scale Economics Vision

- Combined $28 billion revenue, creating the world’s fifth-largest food company

- Massive purchasing power advantages following the economies of scale theory

- Elimination of operational redundancies

- Shared best practices across complementary portfolios

Undervalued Brand Portfolio

- Iconic American brands: Kraft, Heinz, Oscar Mayer, Maxwell House

- Decades of consumer loyalty and pantry penetration

- “Forever” brands that seemed recession-proof

The Fatal Miscalculation: Category Blindness

The partners made a classic strategic error: they assumed that operational excellence could substitute for category-appropriate strategy. Their success in beer and fast food created dangerous overconfidence about the universal applicability of their playbook.

This reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of industry structure analysis. Different industries have different key success factors, and what drives competitive advantage in one category may be irrelevant or even counterproductive in another—a lesson that cost shareholders $57 billion.

The Consumer Preference Velocity Factor

Consumer preference velocity refers to the rate at which consumer preferences change within a specific category or market. Unlike traditional market analysis that focuses on the direction of change, velocity analysis examines the pace and acceleration of preference shifts. This concept proves critical for strategic timing because it determines whether companies can adapt existing strategies or must fundamentally restructure their approaches.

In the Kraft Heinz case, the clean label movement represents a high-velocity shift in preference that began decades before the 2015 merger. The strategic miscalculation wasn’t failing to recognize this trend—it was underestimating how far advanced and irreversible it had become. Understanding preference velocity helps explain why the same operational excellence strategy succeeded in beer (where major preference shifts emerged post-2015) but encountered entrenched resistance in processed food. We can identify three distinct periods along the timeline of the clean label revolution.

Pre-2015 Foundation (The Writing on the Wall)

- 1980s: Clean label movement begins with E-number avoidance in Europe

- 2010: Heinz launches “Simply Heinz,” removing high fructose corn syrup

- 2011: Dramatic increase in mentions of “clean label” in Food Technology Magazine

- 2014: Consumer advocacy successfully pressures major brands (Subway removes azodicarbonamide)

2015-2020 Acceleration (The Perfect Storm)

- 2015: Institute of Food Technologists declares clean label “the only method to adopt”

- 2016: “Clean label” becoming mainstream, shifting from niche to customer expectation

- 2020: Euromonitor estimates global clean label sales at $180 billion

2020-2025 Mainstream Adoption (The New Normal)

- 2025: 83% of US consumers read food labels before making a purchase decision

- 2025: FDA moves to phase out petroleum-based synthetic dyes

- Multiple state AGs investigate food companies for misleading health claims

- Consumer demand weakens for core Kraft Heinz products: Lunchables, Capri Sun, macaroni and cheese, and mayonnaise

The Strategic Attribution Analysis

Was this a category problem accelerated by velocity, or a velocity problem that could have been managed with different strategic choices? The evidence reveals a more nuanced answer: Strategic timing, not category structure alone, determined the value destruction.

Consider Clayton Christensen’s theory of disruptive innovation, which distinguishes between two types of innovation pressure. Sustaining innovation involves enhancing products along dimensions that mainstream customers already value—such as better performance, quality, or features — within existing paradigms. Disruptive innovation creates new markets by offering simpler, more convenient, or more affordable alternatives that initially serve niche segments before expanding to serve broader market segments.

Kraft Heinz faced what Christensen would classify as intense “sustaining innovation” pressure—the need to continuously improve products along dimensions that mainstream customers increasingly valued (cleaner ingredients, transparency, health benefits). However, 3G’s operational excellence playbook treated it as a “low-end disruption” problem, focusing on cost reduction and efficiency rather than performance improvement along these new consumer-valued dimensions.

This misalignment explains why cost-cutting couldn’t solve the strategic challenge. When consumers demand better ingredient profiles and transparency, operational efficiency alone cannot deliver the required improvements. The innovation pressure required reformulation, sourcing changes, and communication strategies—investments that directly conflicted with zero-based budgeting approaches.

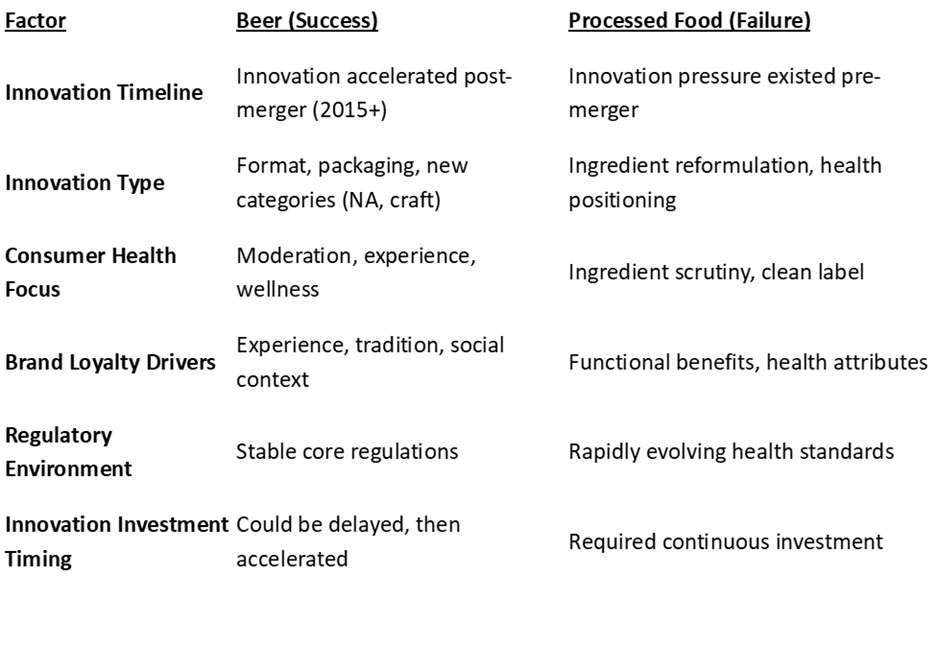

Beer vs. Food: The Critical Structural Differences

The Beer Innovation Paradox: Why Timing Matters More Than Category

A deeper examination of the beer industry reveals a critical insight that refines our understanding of the Kraft Heinz failure. The beer industry has actually undergone massive innovation, particularly since 2015:

- Non-alcoholic beer: 26% annual growth with advanced de-alcoholization technology

- Packaging innovation: Slim cans, sustainable materials, smart packaging technologies

- Flavor experimentation: Exotic ingredients (guava, cardamom, hibiscus), hybrid fermentation methods

- Technology integration: AI-driven brewing, automated systems, VR brewery tours

- Format diversification: Self-pour taprooms, hard seltzers, beer-wine hybrids

- Experience innovation: Michelin-starred brewery restaurants, community hubs

The success of the 3G strategy in beer wasn’t due to minimal innovation requirements—it succeeded because beer’s central innovation pressure began after operational excellence was established. AB InBev could absorb substantial innovation costs because they had already achieved scale economies and operational efficiency.

This reveals the Dynamic Capabilities principle: operational excellence can enable innovation investment, but sequencing is critical. When efficiency gains precede innovation pressure, companies can fund new capabilities from cost savings. Kraft Heinz faced the opposite scenario—innovation pressure that predated their efficiency implementation by over a decade, creating an expensive strategic learning experience.

The Failed $143 Billion Bid: A Strategic Counterfactual

A strategic counterfactual is an analytical framework that examines alternative strategic paths not taken, allowing us to understand why certain strategic choices were made and what different outcomes might have resulted from alternative decisions. By examining what might have happened if Kraft Heinz had successfully acquired Unilever, we can gain a deeper understanding of the fundamental strategic challenges the company faced.

In 2017, Kraft Heinz attempted to acquire Unilever for $143 billion—a move that would have created a global consumer goods colossus. Unilever CEO Paul Polman rejected the offer, stating he “couldn’t think of two more opposite philosophies coming together.”

Polman’s Prescient Analysis:

- Unilever’s focus on sustainable brands and purpose-driven innovation

- Long-term investment in R&D and brand building

- Recognition that cost-cutting alone wouldn’t work in evolving consumer markets

The Counterfactual Analysis: What If the Acquisition Had Succeeded?

Potential Short-Term Benefits:

- Innovation Portfolio Acquisition: Unilever’s genuinely innovative, health-focused brands (like Ben & Jerry’s sustainable initiatives, Dove’s real beauty campaigns) could have provided immediate credibility in evolving consumer segments

- Geographic Risk Diversification: Unilever’s strong emerging market presence might have reduced dependence on mature North American food categories

- Scale for Dual Strategies: The combined entity’s massive scale could theoretically have supported both cost optimization in legacy products and innovation investment in growth categories

Likely Strategic Conflicts:

- Cultural Destruction: 3G’s zero-based budgeting culture would likely have dismantled Unilever’s innovation ecosystem, eliminating the very capabilities that made the acquisition valuable

- Innovation Disinvestment: The combined pressure to deliver immediate synergies would have forced cuts to Unilever’s R&D and brand-building investments

- Talent Exodus: Unilever’s innovation-focused leadership would likely have departed, taking institutional knowledge with them

The acquisition might have temporarily masked Kraft Heinz’s fundamental strategic mismatch by adding genuinely innovative brands. Still, it would ultimately have destroyed Unilever’s innovation culture while failing to address the core timing problem—the result: a larger organization with the same strategic contradictions, potentially destroying even more shareholder value.

The wisdom of Polman’s rejection becomes clearer in hindsight. Even Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway eventually recognized the strategic mismatch—in 2025, Berkshire announced it would no longer hold board seats at Kraft Heinz, a move industry watchers viewed as paving the way for fundamental changes.

This rejection highlights the organizational culture dimension of strategy. Successful mergers require not only financial synergies but also cultural compatibility, particularly in terms of innovation orientation and customer focus.

Strategic Lessons for Today’s Business Leaders

The Kraft Heinz experience offers a masterclass in strategic timing, category dynamics, and the complex relationship between operational excellence and investment in innovation. Rather than simply cautioning against operational efficiency strategies, the case offers more nuanced insights into when different strategic approaches succeed or encounter resistance.

The following five lessons extend far beyond food and beverage companies. In an era where consumer preferences accelerate across virtually every industry—from sustainability demands in fashion to privacy concerns in technology—understanding the strategic principles demonstrated by Kraft Heinz becomes essential for any business leader navigating market evolution.

Figure 2. Kraft Heinz: The Strategic Insight

1. Category Selection Trumps Operational Excellence

Before applying any proven strategy, rigorously assess whether the category structure supports your approach using Porter’s Five Forces analysis.

Application Questions:

- What drives competitive advantage in this specific category?

- Are consumer preferences stable or evolving rapidly?

- Does success require operational excellence, innovation excellence, or both?

- How do regulatory and social trends affect the basis of competition?

2. Strategic Timing and Innovation-Efficiency Sequencing

Success depends on understanding both when innovation pressure begins relative to strategic implementation and how different types of innovation requirements affect the sequencing of operational excellence and innovation investment.

Diagnostic Questions for Strategic Timing Assessment:

- When did innovation pressure begin in this category relative to strategy implementation?

- What type of innovation drives competitive advantage (format, experience, ingredients, technology)?

- Can innovation investment be delayed and then accelerated, or must it be continuous?

- How patient are consumers with established brands that temporarily reduce innovation?

- Do consumers evaluate functional attributes (ingredients) or experiential attributes (format, context)?

- Can efficiency gains fund innovation investment, or do both compete for resources?

3. The Buffett Investment Philosophy Challenge

Even legendary long-term investment approaches can fail when structural shifts change the basis of competition faster than patient capital can adapt.

The Kraft Heinz experience challenged one of investing’s most revered philosophies. Warren Buffett’s approach of buying great businesses and holding them “forever” met its match when consumer preference velocity exceeded the speed of strategic adaptation. The ultimate validation came in 2025 when Berkshire Hathaway announced it would no longer hold board seats at Kraft Heinz—a tacit acknowledgment that even patient capital has limits when facing structural misalignment.

Framework for Patient Capital Assessment:

- Are you betting on brand heritage or competitive positioning?

- Has the fundamental basis of competition shifted in this category?

- Can long-term ownership overcome short-term strategic misalignment?

- When does “holding forever” become strategically counterproductive?

4. When Integration Destroys Value

Some business combinations create more value as separate entities than as integrated operations—a violation of the synergy assumption in mergers and acquisitions (M&A).

When to Consider Separation:

- Business units require fundamentally different strategies

- Consumer bases have diverging preferences

- Operational requirements conflict (efficiency vs. innovation)

- Different capital allocation priorities exist

5. Brand Heritage vs. Consumer Evolution

“Forever brands” aren’t forever if they can’t evolve with dynamic consumer expectations, challenging the brand equity’s assumption.

Evolution Strategies:

- Continuous formulation improvement

- Transparent communication about changes

- Investment in consumer education

- Willingness to cannibalize existing products

Implications for Different Industries

The strategic principles revealed by the Kraft Heinz experience extend across industry boundaries, offering insights for any organization facing the tension between operational efficiency and innovation investment. As consumer preferences accelerate and competitive dynamics evolve across sectors, leaders must understand how these lessons apply to their specific contexts.

The following industry analysis demonstrates how the timing-sequencing framework can help organizations avoid similar strategic misalignments while building capabilities for both operational excellence and innovation agility.

Retail Companies

- Risk: Assuming private label strategies work across all categories

- Mitigation: Category-by-category analysis of whether efficiency or innovation drives value

Technology Companies

- Risk: Applying hardware efficiency models to software innovation challenges

- Mitigation: Separate operational excellence from innovation investment; maintain ambidextrous organization capabilities

Healthcare Companies

- Risk: Cost-cutting in the face of regulatory and efficacy evolution

- Mitigation: Protect innovation investment even during efficiency drives

Financial Services

- Risk: Operational consolidation eliminating digital innovation capacity

- Mitigation: Recognize that efficiency and customer experience innovation require different organizational capabilities

The Broader Business Environment Implications

The Kraft Heinz experience reflects broader industry dynamics that extend well beyond food and beverage companies. The strategic principles revealed here—about timing, consumer velocity, and the limits of operational excellence—are playing out across multiple sectors as companies grapple with similar tensions between efficiency and innovation demands.

The Industry-Wide Restructuring Wave

Kraft Heinz isn’t alone in recognizing that some business combinations create more value as separate entities. The food industry is experiencing a wave of strategic restructuring that validates the core insights from the Kraft Heinz experience. Mars recently completed a $30 billion acquisition of Kellanova (spun out of Kellogg), which houses faster-growing snack brands like Pringles and Cheez-It. Meanwhile, Kellogg’s slower-growing North American cereal business, renamed WK Kellogg, was sold to Italian candy maker Ferrero for $3 billion.

This pattern demonstrates that successful companies are increasingly willing to separate business units with different innovation requirements and growth trajectories—exactly the strategic correction Kraft Heinz is now implementing.

The Rise of Category-Specific Strategies

The Kraft Heinz experience demonstrates that even proven operational excellence strategies require careful adaptation to category-specific innovation cycles and the velocity of consumer preferences. The food industry’s current challenges—inflation-weary consumers switching to store brands, government scrutiny of processed foods, the rise of weight-loss drugs, and cuts to food-stamp programs—demonstrate that successful investors increasingly need:

- Category expertise alongside operational excellence

- Consumer trend analysis capabilities

- Innovation assessment skills

- Portfolio complexity management

The Innovation Investment Imperative

In categories where consumer preferences evolve rapidly—accelerated by factors like health consciousness, regulatory changes, and economic pressures—companies must:

- Protect innovation investment during efficiency drives

- Build dual capabilities for both operational excellence and innovation

- Accept higher complexity in exchange for strategic flexibility

- Develop consumer sensing mechanisms to identify preference shifts early

The Future of Corporate Strategy

The case demonstrates several emerging strategic principles:

- Industry structure analysis must precede strategy selection

- Consumer velocity assessment is now a core strategic capability

- Portfolio complexity sometimes creates more value than integration

- Proven strategies may not transfer across categories or time periods

Conclusion: The $57 Billion Lesson in Strategic Timing

The Kraft Heinz story represents one of business history’s most expensive lessons in strategic sequencing rather than simple strategic misjudgment. While the partnership of Buffett’s patient capital and 3G’s operational excellence seemed like a dream team, they encountered innovation pressure that predated their efficiency implementation by over a decade.

The beer industry’s massive wave of innovation since 2015—from AI-driven brewing to a 26% annual growth in non-alcoholic beer—proves that 3G’s approach can work even with significant innovation requirements, provided the sequencing is correct. AB InBev’s continued success stems from having established operational excellence before major innovation pressure emerged, allowing cost savings to fund new capabilities.

The planned breakup isn’t an admission of failure—it’s a strategic correction that acknowledges different businesses require different approaches to the innovation-efficiency balance. By separating entities with different timing requirements and innovation profiles, Kraft Heinz may finally unlock the value that ten years of forced integration couldn’t achieve.

The Organizational Ambidexterity Alternative

This raises a critical question: Could Kraft Heinz have succeeded by developing organizational ambidexterity—the ability to simultaneously manage efficiency and innovation within the same organization? James March’s seminal work on “exploration and exploitation” suggests that successful organizations must balance both capabilities. Still, the Kraft Heinz experience reveals why this approach may not have been viable in their specific context.

Why Ambidexterity Wasn’t an Option for Kraft Heinz:

Resource Competition: True ambidexterity requires ring-fenced resources for innovation while maintaining operational efficiency. Kraft Heinz’s zero-based budgeting approach inherently conflicted with the resource protection needed for sustained innovation investment.

Cultural Incompatibility: The 3G culture of extreme cost discipline created organizational antibodies against experimentation and “intelligent failure,” which are required for innovation. Research shows that ambidextrous organizations require leaders who can manage the tensions between different operational modes—a capability that Kraft Heinz lacked the time to develop.

Time Pressure: Organizational ambidexterity typically requires 3-5 years to develop effectively. Kraft Heinz faced immediate innovation pressure that had been building for over a decade, making this a luxury they couldn’t afford.

Structural Complexity: Managing parallel organizations (one focused on efficiency, another on innovation) within the same entity requires sophisticated governance structures and leadership capabilities that the combined organization had not yet developed.

The Broader Implications for Industry Leaders:

However, for organizations facing similar challenges but with more favorable timing, developing ambidextrous capabilities may offer a path forward. Companies in industries where preference velocity is accelerating—such as technology, healthcare, and financial services—should consider whether they can build parallel organizational capabilities before encountering the innovation pressure that Kraft Heinz faced too late.

The key insight is that organizational ambidexterity is most effective as a proactive strategy, rather than a reactive solution. Organizations that develop these capabilities during periods of relative stability can better navigate subsequent periods of rapid change.

For today’s business leaders, the lesson transcends simple category analysis: operational excellence and innovation investment can coexist, but sequencing determines outcomes. The most dangerous strategy isn’t necessarily applying good tools to the wrong category—it’s applying the right tools at the wrong time in the competitive cycle.

As we watch Kraft Heinz attempt to resurrect value through separation, we’re witnessing a real-time case study in strategic evolution: the recognition that timing, not just capability, determines whether proven strategies create or destroy value. In an era of accelerating change across all industries, this distinction has never been more critical—or more expensive to overlook.

#StrategicTiming #BusinessStrategy #KraftHeinz #OperationalExcellence #InnovationStrategy #ExecutiveLeadership #MergersAndAcquisitions #CPGStrategy #StrategicExecution #BusinessTransformation #TopRetailExpert

This analysis examines one of business history’s most expensive strategic lessons, drawing insights from industry reports, consumer trend data, and competitive dynamics across the food and beverage sectors. The strategic frameworks and tools referenced connect to broader principles of strategic management that apply across various industries and contexts.

About the Author: Dr. Mohamed Amer is a strategy advisor with over 25 years of experience spanning military leadership, global corporate roles, entrepreneurial ventures, and academic research. As a Certified Chair™ Executive, RetailWire BrainTrust panelist, and RETHINK Retail Top Retail Expert, he brings a uniquely integrated perspective to strategic challenges. As an Adjunct Professor at Pepperdine Graziadio Business School and a Fellow at the Social Institute for Social Innovation at Fielding Graduate School with a Ph.D. in Human and Organizational Systems and executive experience at SAP, he bridges rigorous academic insights with practical business applications.

Ready to strengthen your organization’s strategic practices? Schedule a 30-minute Strategic Practice Assessment to evaluate your current capabilities and identify areas for improvement.

Strategy Doctor offers advisory services that incorporate cutting-edge strategic perspectives, enabling organizations to develop more effective strategies in complex environments. Visit StratDoc.co to learn more.

Select Sources

Christensen, C. M. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma. Harvard Business Review Press.

Christensen, C. M., & Raynor, M. E. (2003). The innovator’s solution. Harvard Business Review Press.

Clean label: The next generation. (2011, February). Food Technology Magazine, 65(2).

Euromonitor International. (n.d.). Clean label: Positioning for the global packaged food market.

FDA announces timeline for synthetic dye review. (2025, January). Food Safety News.

Gibson, C. B., & Birkinshaw, J. (2004). The antecedents, consequences, and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Academy of Management Journal, 47(2), 209-226.

Grand View Research. (2024). Non-alcoholic beer market growth analysis.

Heinz launches Simply Heinz ketchup. (2010, March). Food Business Magazine.

March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71-87.

March, J. G. (1996). Continuity and change in theories of organizational action. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(2), 278-287.

O’Reilly III, C. A., & Tushman, M. L. (2013). Organizational ambidexterity: Past, present, and future. Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(4), 324-338.

Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 on food additives. European Parliament.

State of California Attorney General. (2024-2025). Press releases.

Subway to remove chemical from bread after protest. (2014, February 6). Associated Press.

The business case for clean label. (2020, March). Euromonitor.

Unilever and Kraft Heinz: A clash of (corporate) culture. (2017, February 21). ICMA Center